By Molly Bergum

December 14, 2018

Meet the Round Leaved Orchid

There are two species of round leaved orchids at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest: the greater round leaved orchid (Platanthera macrophylla) and the lesser round leaved orchid (Platanthera orbiculata). These distinct species interbreed to create hybrids, which also exist in the forest. Round leaved orchids undergo several discrete life stages, including an underground stage, one-leaf stage, two-leaf stage, and flowering stage. When they are flowering, they have two large, circular leaves and a flower spike. The spike is an inflorescence that typically contains between five and 30 individual flowers.

A close-up view of an orchid flower illustrates its three petals and three sepals. The side view shows the long, tubular spur that falls behind the floral orifice. Photos: Nat Cleavitt

The long spur that tails behind each flower contains nectar that allures insects to the flower and rewards them for their pollination services. A compatible pollinator must have a proboscis that can extend the length of the spur to retrieve the nectar. Researchers hypothesize that two noctuid moths, the large looper moth (Auotographa ampla) and the green-patched looper moth (Diachrysia balluca), pollinate lesser rounded leaved orchids, based on the size of their mouthparts. Botanists have also debated whether sphinx moths pollinate greater round leaved orchids, based on uncited claims from the 1890s.

The different round leaved orchid species are primarily distinguished based on their spur lengths. According to a study based on herbaria specimens, great round leaved orchids have spurs that are 28 mm or greater, while lesser round leaved orchids have spurs that are less than 28 mm. However, this boundary is less clear with the observation that interspecific hybrid orchids exist, generally with medium-length spurs.

Assessing the Threat

During the summer of 2018, I worked with Hubbard Brook Investigator and Vegetation Crew Leader, Nat Cleavitt, to explore the extent of deer herbivory on round leaved orchids at Hubbard Brook. According to Nat, who has been closely following the orchids for several years, the number of orchid spikes being eaten by deer has increased dramatically, and deer herbivory is a keen threat to orchid conservation. Furthermore, the threat from deer could become even more severe as milder winters are less constraining to their population growth. Additional research was necessary to understand the magnitude of risk the orchid population faces due to deer. The objective of the experiment was to find out if cages were an effective way of protecting orchids from being eaten by deer without preventing pollinators from reaching the flowers.

REU student Molly Bergum adjusts a game camera that is focused on an uncaged orchid in Watershed 1. The uncaged orchid's pair sits in a cage in the foreground. Photo: Nat Cleavitt

For the study, we identified 55 pairs of orchids within nine different sites at Hubbard Brook. The paired orchids, which were designated based on their close proximity within the same site, included one caged orchid and one uncaged orchid. We cut three holes into every cage in case large moths were pollinators. We also installed a motion-triggered game camera on one orchid in every site and visited the orchids weekly to monitor herbivory and pollination. The research that was conducted on the Hubbard Brook orchids was made possible through a National Science Foundation (NSF)-sponsored Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) project.

The Who’s Who of Orchid Visitors

Herbivores

White-tailed deer present a severe threat to orchids because of how quickly they can destroy the entire above-ground portions of the plant. Game cameras captured deer eating orchids twice at Hubbard Brook over the summer. A surprising finding was that the deer appear to be startled by the clicking emitted from the camera and in some cases left the vicinity after noticing the camera.

A game camera shows a deer spotting an orchid from the other side of a boulder on July 5. Upon coming closer, the deer consumes the orchid spike. The deer then continues by eating the leaves. Photos: Reconyx Game Camera

On July 24, a game camera captures a deer consuming a previously healthy orchid through the rain. After the deer leaves, the plant is left bereft of all flowers and both leaves. Photos: Moultrie Game Camera.

A deer leans in to examine an orchid on October 10. After appearing to be startled by the camera, it leaves. Photos: Moultrie Game Camera, courtesy of Nat Cleavitt

Pollinators

Multiple potential pollinators visited the orchids and were likely drawn to the flowers for a taste of nectar. While no current literature cites the following insects and birds as pollinators of round leaved orchids, the species have been recorded as pollinators of other orchids.

We observed and photographed a geranium plume moth on a round leaved orchid flower. Two species of plume moths are thought to be pollinators of the sparse-flowered bog orchid (Platanthera sparsiflora), which is an orchid similar to the round leaved orchids.

We also witnessed a small carpenter bee visiting flowers on a round leaved orchid spike. Small carpenter bees are cited as pollinators for several orchids in the Cypripedium genus. Alternatively, botanists hypothesize that they steal nectar from the yellow fringed orchid (Platanthera ciliaris) by creating slits in the spurs that they use to extract nectar without pollinating the flower.

A lesser carpenter bee stops on a flower on July 16. Photo: Nat Cleavitt

A game camera captured a female ruby-throated hummingbird hovering around a flower spike, drinking nectar from many flowers. There is a scarce amount of information concerning the pollination of North American orchids by hummingbirds, but hummingbirds are the pollinators of several tropical orchids.

A ruby-throated hummingbird hovers near several flowers on a roundleaved orchid spike. Photo: Moultrie Game Camera.

Key Findings

Herbivores

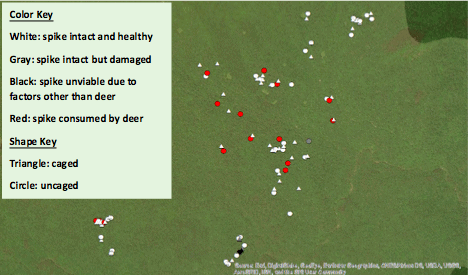

Deer herbivory was a major concern to orchid spikes, although the severity was unequal at the different sites. The birder mid grid west of Watershed 6 saw the most extreme deer herbivory, with every uncaged orchid in the study being completely eaten by the last week in July. Overall, 29 percent of the uncaged orchids were eaten by deer. Deer herbivory is likely to become exacerbated as deer populations at Hubbard Brook increase.

Additional threats to the orchids included being broken by falling debris and being consumed post-pollination by fungus and insects.

A map shows the locations of the caged and uncaged orchids in the study at Hubbard Brook. The statuses of the floral spikes as of August 7 are coded by color.

Pollinators

Contrary to concerns about cages excluding pollinators, caged orchids had a significantly higher percent of pollinated flowers than those without cages when the orchid pairs that were not eaten during the study were compared. The disparity indicates that the cages can be used as a solution to herbivory without sacrificing pollination success.

Additionally, the observations of multiple potential pollinators are significant because there is currently a scarcity of direct evidence pertaining to which species pollinate round leaved orchids. Charles Darwin hypothesized that many orchids coevolve with specific pollinators in order to prevent pollen from being wasted in the flowers of different species. However, it can be a disadvantage for an orchid to rely on a specific pollinator if that pollinator doesn’t have the same level of dependence on the orchid. While current literature suggests that the round leaved orchids have a relationship with pollination specialists, the observations at Hubbard Brook this summer suggest that the orchids may have several generalist pollinators. Additional research is necessary to ascertain how a generalist pollination system could impact the diversity and evolution of round leaved orchids.

References

Argue C. 2012. The Pollination Biology of North American Orchids: Volume 1. New York: Springer.

Bergum M, Cleavitt N, and Matthews D. 2018. Frontiers Ecopics: An unexpected visitor. Front Ecol Environ 16 (9): 502.

Campbell JL, Mitchell MJ, Groffman PM, Christenson LM, and Hardy JP. 2005. Winter in northeastern North America: a critical period for ecological processes. Front Ecol Environ 3: 314-322.

Cleavitt NL, Berry EJ, Hautaniemi J, and Fahey TJ. 2017. Life stages, demographic rates, and leaf damage for the round -leaved orchids, Platanthera orbiculata (Pursh.) Lindley and P. macrophylla (Goldie) PM Brown in a northern hardwood forest in New Hampshire, USA. Botany 95 (1): 61–71.

Micheneau C, Johnson SD, and Fay MF. 2009. Orchid pollination: from Darwin to the present day. Bot J Linn Soc 161: 1–19.

Reddoch A and Reddoch J. 1993. The species pair Platanthera orbiculata and P. macrophylla (Orchidacea): taxonomy, morphology, distributions, and habits.