The Ash Protection Experiment (APE) is a major new research initiative at Hubbard Brook. This article provides background about the experiment and answers frequently asked questions. Written by Raisa Kochmaruk and Matt Ayres; illustration by Raisa Kochmaruk. 2023.

There are about 26,000 white ash trees in the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest. They are the biggest and tallest trees in the forest, with diameters that can exceed 50 inches and crowns that surpass 100 feet. In the next decade, emerald ash borers will kill almost all of them. Klooster et al. reported > 99% of ash in similar forests in Michigan. When the ash trees die, they will be replaced by the beech, sugar maple, and yellow birch with which they now comingle. Fifty years from now, it will take a skilled observer to recognize the places where ash trees died. But will the forest be different? Or is one tree as good as another? To an ecologist this is the question of niches vs. ecological redundancy. This long-standing technical question has never been more pertinent than in the Anthropocene, where forests all over the world are being rocked by changes in atmosphere, climate, land use, and the rising tide of non-native species (such as the emerald ash borer). The ash protection experiment (APE) was implemented last year in the Hubbard Brook Forest to study the ecological effects of a tree species elimination as has never before been possible. Researchers plan for the study to be active for many decades, and to generate new data and new knowledge that is globally unique and globally relevant.

Frequently Asked Questions

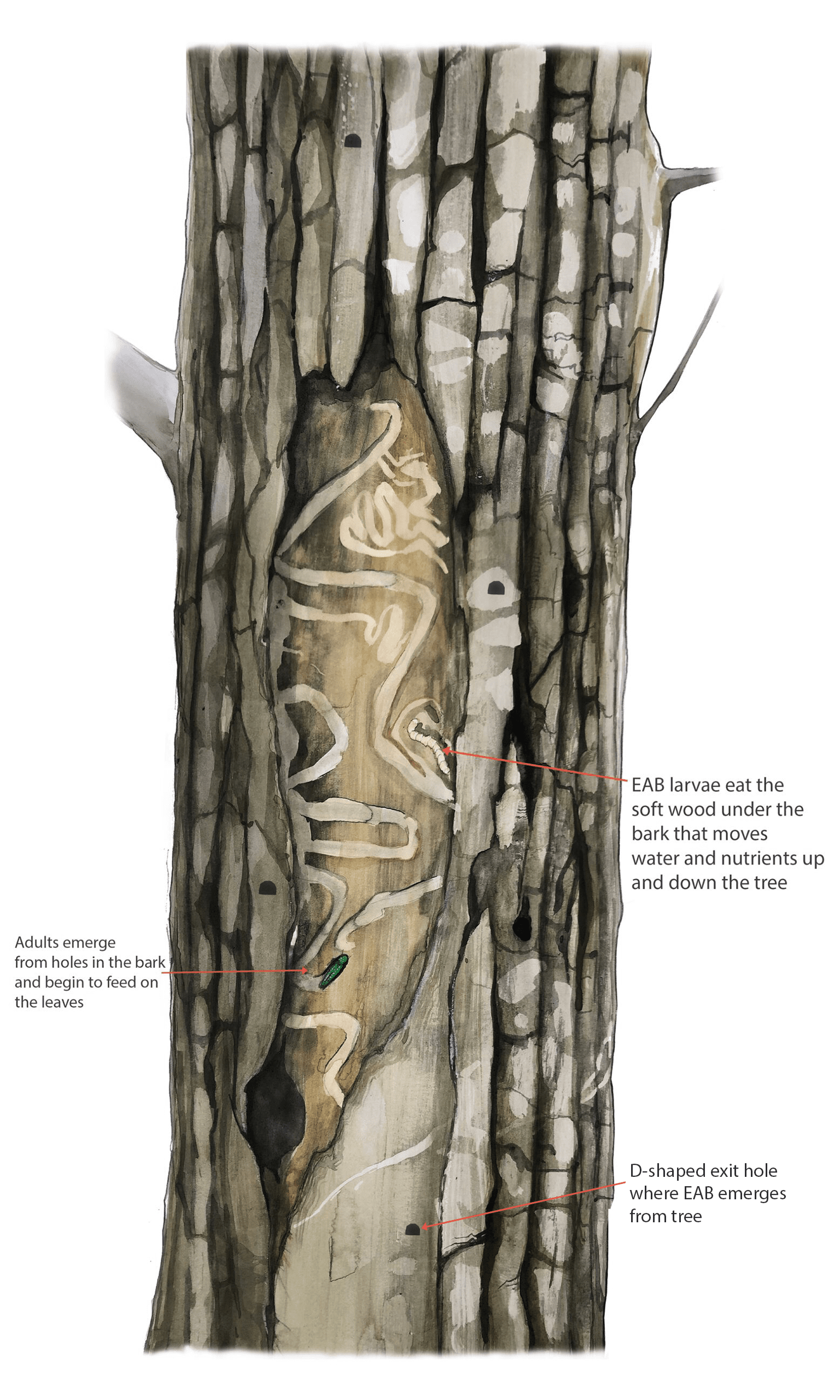

What is the EAB, and how does it kill trees?

The emerald ash borer (EAB) is a jewel beetle from northeastern Asia that feeds on ash species. EAB spreads through the transport of wood products, including shipping palettes, and was first discovered in the US in Michigan in 2002. It has since been reported in 36 states. EAB lays eggs in bark crevices on ash trees, and the larvae feed on the layer of the tree that moves water and nutrients just underneath the bark. Larvae emerge as adults in one to two years.

What is Emamectin benzoate?

Emamectin benzoate is a synthetic molecule derived from a compound produced by naturally-occurring soil bacteria. The chemical is commonly used in agriculture and aquaculture and poses low toxicity to vertebrates. Systemically injected emamectin benzoate, commercially known as the pesticides TREE-age and ArborMectin, is the most effective insecticide against EAB compared to the pesticides imidacloprid (Imicide), azadirachtin (TreeAzin and Azasol) and dinotefuran (Safari) products.

How is Emamectin benzoate administered?

Researchers drill evenly spaced holes at a slight downward angle where the roots of the ash tree attach to the trunk, being careful to avoid dead or damaged tissues that won’t take up the pesticide. Compressed air is used to deliver insecticide into holes fitted with one-way valves. Trees will grow over these holes within a year.

How much pesticide is injected into trees?

The pesticide injected into the trees only contains 4% of the active ingredient. Injected volumes are low and the chemical is much more targeted when compared with alternative treatments, such as bark or soil drenches, or leaf application. Much of the chemical becomes bound to tree tissues in the xylem or in the leaves.

Can the pesticide be detected after injection?

Low concentrations of the pesticide are detectable in falling leaves but degrade quickly, especially when exposed to sunlight. Preliminary analyses have shown that the chemical is below minimum detection limits (1 part per billion) in the soil, although it may persist in low concentration in the leaf litter for a short period of time.

How does the pesticide impact arthropod communities?

Preliminary studies do not indicate major changes in soil arthropod biodiversity or community structure; this is currently under investigation.

Does the pesticide advance up the food chain?

Since EAB feeding on treated ash tend to die quickly, they generally do not develop or become large enough to be fed on by birds or other insectivores.

Who are the participants?

The Ash Protection experiment is an open collaboration that enthusiastically invites new participants. Current participants represent many institutions, including Arborjet, Boston University, Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Harvard Forest, Hubbard Brook Research Foundation, Northern Research Station of the USDA Forest Service Syracuse, University of Connecticut, University of New Hampshire, and White Mountain National Forest.

About the Ash Protection Experiment

The predominant questions in the Ash Protection Experiment are:

- How will the forest composition shift around dead and dying ash trees in comparison to plots with healthy ash trees?

- What tree species will replace ash trees' position in the canopy?

- How will the soil community change with the decline of the microorganisms that thrive on ash roots?

- How will spring ephemeral communities be affected?

Experiment Design

Investigators identified 68 groves of ash trees (20 meters in diameter) that were distributed throughout the forest and across the two most common soil types (Bh podzol and typical podzol). About half of the ash plots on each soil type were randomly selected for protection against emerald ash borer via injection with the pesticide emamectin benzoate. All ash trees within and around treatment study plots were protected. The pesticide remains in the phloem (inner bark) for about four years where it quickly kills any beetles that try to feed on these trees. Treatments will be repeated at four-year intervals.

Regular measurements of the protected and exposed ash plots will capture changes in soil composition, forest structure, species diversity, and chemical processes as the ash trees die and are replaced by other trees. Among other things, this will be the first experimental study of how tree species shape forest soils and how forest soils influence forest biota, and the features of forests that matter to people.